Russian Post investing to meet consumer demand

Denis Ilin, a former executive with Russia’s Volga-Dnepr Group and its AirBridgeCargo subsidiary, is applying his airfreight knowledge at Russian Post, to optimise e-commerce logistics.

As deputy CEO for international business at Russian Post, Ilin is responsible for cross-border traffic, mainly for small packages sent to Russia by e-commerce platforms using a traditional postal channel to process, handle and deliver for the last mile.

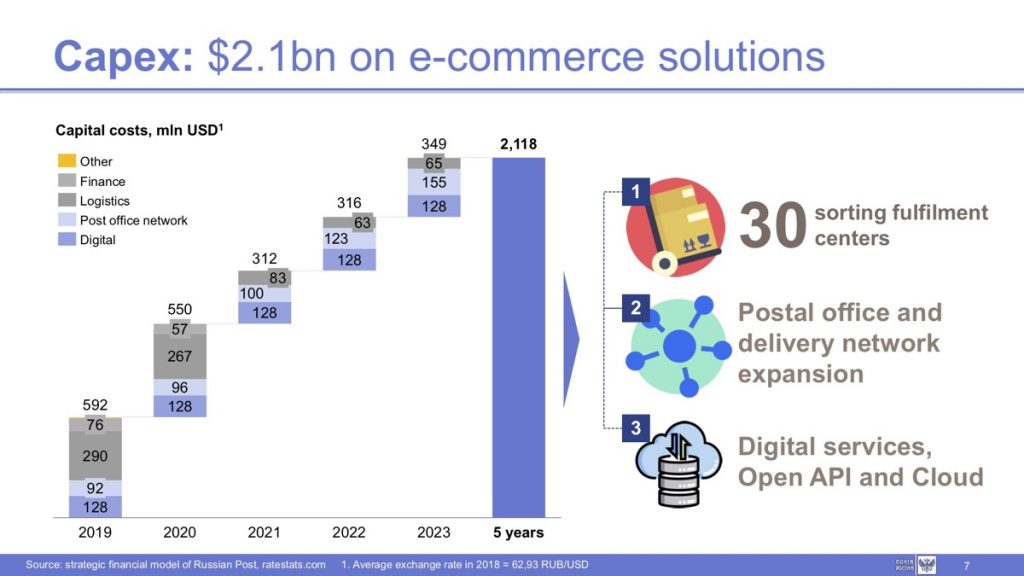

Russian Post plays a very important role in domestic delivery business, with an 81% market share last year of all cross-border traffic into Russia. It has big plans and will spend $2.2bn in capital expenditure over five years to 2023 to handle e-commerce traffic.

The investment includes 30 additional sorting fulfilment centres, expansion of the post office and delivery network, plus development of digital services, open application programming interface (API) and cloud-based systems.

Speaking on the side-lines of the Air Cargo Europe in Munich, Rogistics met up with Ilin who outlined the challenges and opportunities in his new role.

“Russian Post, being the national postal service, has a dominating position in terms of handling postal shipments which enjoy and benefit from simplified customs procedures for all business to consumer (B2C) imports, and is the first choice for e-commerce logistics providers.”

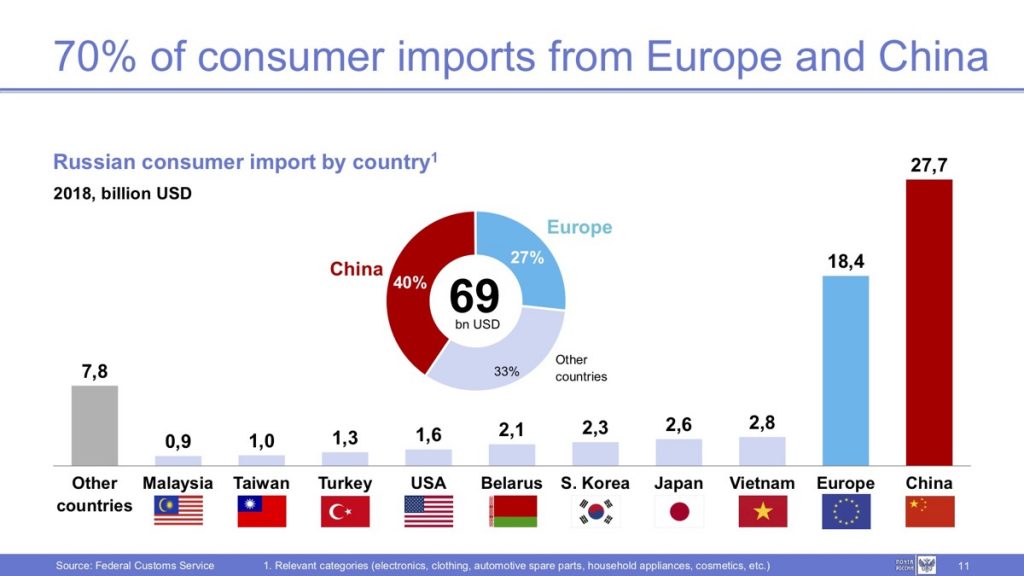

The current focus is on China which in 2018 accounted for some 65% of all traffic volume entering Russia in terms of the number of individual shipments. In value terms, Chinese imports were worth $27.7bn in 2018, or some 40% of the total inbound value of $69bn, while European imports were in second place, at $18.4bn or 27% of the import market.

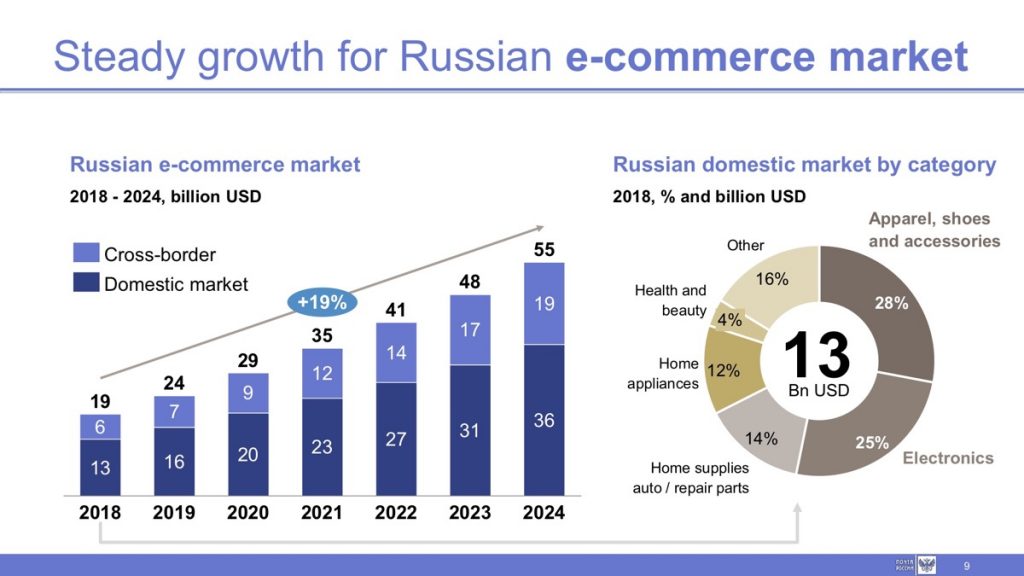

The forecast is for steady growth in Russian e-commerce consignments, rising from $19bn by value in 2018 to $55bn by 2024, with cross-border traffic increasing from 6% to 19% of all shipments in the same six year period.

Said Ilin: “Naturally, my key customer is Alibaba Group, and Russian Post handles 93% of all [inbound] Alibaba shipments in 2018.”

Hence the strategic decision by Russian Post to invest in e-commerce, with the goal of 1-3 day delivery for 80% of all such deliveries across Russia by 2024, with the national postal business achieving an average 3.3 day parcel delivery in 2018, shaving a day off the average of 4.3 days in 2017.

How important are e-commerce delivery times to Russian consumers buying online?

Said Ilin: “If you look at all e-commerce shipments, it is pretty much low-cost logistics and when people buy online, they do not necessarily pay for their goods to be delivered faster, instead they search to find the cheapest product.

“That is the first priority for most online buyers, as a result they sometimes ignore transit times to get the cheaper product, meaning that about 60% of all e-commerce traffic into Russia is going as non-registered mail which is the cheapest and slowest one, with a delivery time up to 30-45 days.

“Russian Post provides several solutions. We fly it, we take it by truck from China to Russia or we will take it by sea from Hong Kong to Vladivostok and then by rail.”

For those with a more pressing delivery need and a higher budget, the demand for track and trace services to monitor a shipment, and guaranteed delivery times, come to the fore.

“For more expensive products we talk about a seven-day delivery time and when we talk about an air cargo logistics solution, we achieve a three-day delivery time. But some 60% of all e-commerce traffic from China into Russia is the cheap stuff and it requires the cheapest possible logistics.”

But market competition is pushing internet providers to offer ‘free’ delivery on those tighter delivery schedules, so the logistics solution will have to meet that challenge.

Unfortunately, that does not mean more use of airfreight but better inventory planning at the local level, using predictive logistics to forecast what the next must-have item will be, even before consumers click the buy-now button on their smart phones.

Predicted logistics analyses marketing information and consumer behavioural trends for internet providers to predict which item will be in demand and to start moving it to potential areas of consumption.

Said Ilin: “It is up to the e-commerce platforms to develop a logistics network to ensure delivery within the required transit time, and that means the products start moving from the second it is ordered online.

“However, that does not mean the product starts moving from the manufacturer, as it might be already sitting in a local warehouse. The platforms manage the inventory and understand evolving demand in specific items. They are already arranging the logistics before it is ordered.”

Said Ilin: “So when they say it is going to be delivered within 72 hours, most likely it is not going to be delivered from China to the UK in 72 hours, but it will be delivered from a local distribution centre to your door. Otherwise the cost of the express logistics might send the prices of e-com goods back up to the level of the traditional offline retail”

Asked about the logistical and economic challenges for a monopoly postal provider in a world where the customer demands the cheapest delivery, Ilin first explained the difference between postal channels and commercial channels, the latter being courier, express or commercial cargo.

“When an item goes B2C it goes by post through a simplified customs procedure which is much lower in terms of what data needs to be presented to a customs officer to make sure that the parcel is cleared.

“And the more information you need, the more complicated it is for a buyer, as some people are very hesitant to give away too much of personal data when they buy online. When it goes by mail, they provide basic information, such as the name, the delivery address and nothing else.

Ilin continued: “When a product goes by an express or courier you have to provide a lot of information: including the tax number and other data, all of which makes the postal service more competitive and attractive to the e-com cross-border industry.”

But with postal simplicity comes a challenge: consumers are benefiting from the cheapest possible logistics because delivery rates between postal companies worldwide are set at a lower tariff in order to be affordable to any citizen in the world.

What was meant to encourage letter correspondence has been usurped in the internet age of global e-commerce.

As a result, large landmass countries, such as Russia, Canada and the US, handle all of this commercial volume but have to deliver it throughout the country at a price which quite often does not cover the true cost.

And that is, probably, the reason why the US Postal Service (USPS) is threatening to withdraw from the Universal Postal Union (UPU), based in Switzerland, established in 1874 and with 192 members from postal services around the world

“The nature of the postal service as such is being compromised and abused by commercial use.

Denis Ilin, Russian Post

The USPS believes that each country should now have the right to set its own international rates for delivering small packages, rather than those set by the UPU.

In other words, the USPS and other postal authorities are targeting e-commerce parcels from China that arrive in consolidations and then piggyback the post offices for cheaper last mile delivery.

Said Ilin: “The nature of the postal service as such is being compromised and abused by commercial use. By providing cheap and affordable rates national postal services are in effect subsidising Chinese exporters and they want the rates adjusted to a market level so that its costs are covered and its economic rationale is not compromised.”

Russia has the same problem, with 50% of its consumers sitting in Moscow and St Petersburg and areas surrounding western Russia.

“I am not surprised in our sorting centre to see a small parcel with some cheap stuff inside, probably originating from China, going to the Hong Kong Post and then flown from Hong Kong to Moscow. The item, which Russian Post then has to deliver from Moscow to the Russian Far East, and you can imagine what cost is attached to this small packet.

“It goes twice the length of the country, from Hong Kong to Moscow, and then from Moscow back to the Far East again, all at my expense.

“I will never be able to charge a rate which covers these costs, and that is a big challenge. Unless I control the traffic flows and the point of origin, I will never cover my costs and the transit time is probably three times longer than necessary, so we also lose on quality

“My biggest challenge at the moment is to ensure that e-commerce logistics are managed in a way that is the most efficient, both in costs and transit times.”

But there is cooperation between some postal services, and Russian Post, for example, has linked up with Deutsche Post for up to eight trucks per day going from Berlin to Moscow with mail, most of it is e-commerce traffic, and there is a similar set up in London.

“Postal services need to go out and offer end-to-end solutions to the direct clients, namely internet platforms and e-commerce consolidators.”

Denis Ilin, Russian Post

Another example is Japan Post, which sends consignments by sea to Vladivostok, and then Russian Post hauls its by train to Moscow, for onward delivery by truck to 13 European destinations.

“We try to handle e-commerce as an end-to-end solution rather than a last mile solution. We are currently talking to China Post about setting up bilateral products which would allow us to control efficiently the logistics chain with a rate that does not distort the market.

“Postal services need to go out and offer end-to-end solutions to the direct clients, namely internet platforms and e-commerce consolidators.”

There are two modes of e-commerce logistics, online and offline. Online is when a platform like Amazon takes your order and handles the logistics itself. Offline is when the merchant allows the internet platform to sell the goods only, and then the merchant organises the delivery, believing that it can do this itself more efficiently and more cheaply by using consolidators.

Said Ilin: “My priority now is the Internet platforms as these are my direct clients, but I do talk to consolidators as well, however for me they are tier 2 customers.”

With his air cargo background, Ilin said that he will try to use land or sea connections as much as possible, with bellyhold the primary air cargo mode because of its price and connections, adding that freighters are always expensive.

He highlighted another dilemma for freighters, in that e-commerce providers will pay only actual weight for their volumetric cargo, which is why e-commerce uses freighters mainly during peak season demand.

He concluded: “E-commerce logistics is low cost and it always will be, but low-cost solutions do not exist in airfreight. Air cargo people still think in business to business (B2B) terms whereas for us it is B2C and it requires a completely different approach.

“The air cargo industry can complain about it and probably dislike it, but it doesn’t matter, the market has changed and unless the airfreight adjusts accordingly, it will keep losing its market share to e-commerce players which operate their own or controlled ACMI fleets.”